March 11, 2018

By Ahmad Rafat

International Women’s Day (IWD) is celebrated on March 8 every year. It commemorates the movement for women’s rights. The tradition dates back to 1909, when women’s day was first observed in New York. The event was officially adopted by the United Nations in 1975.

Recent protests by workers and women in Iran have given the IWD particular significance this year. The “Girls of Enqelab Street” has arguably been the most creative movement against one of the cornerstones of the Islamic Republic, namely the compulsory hijab.

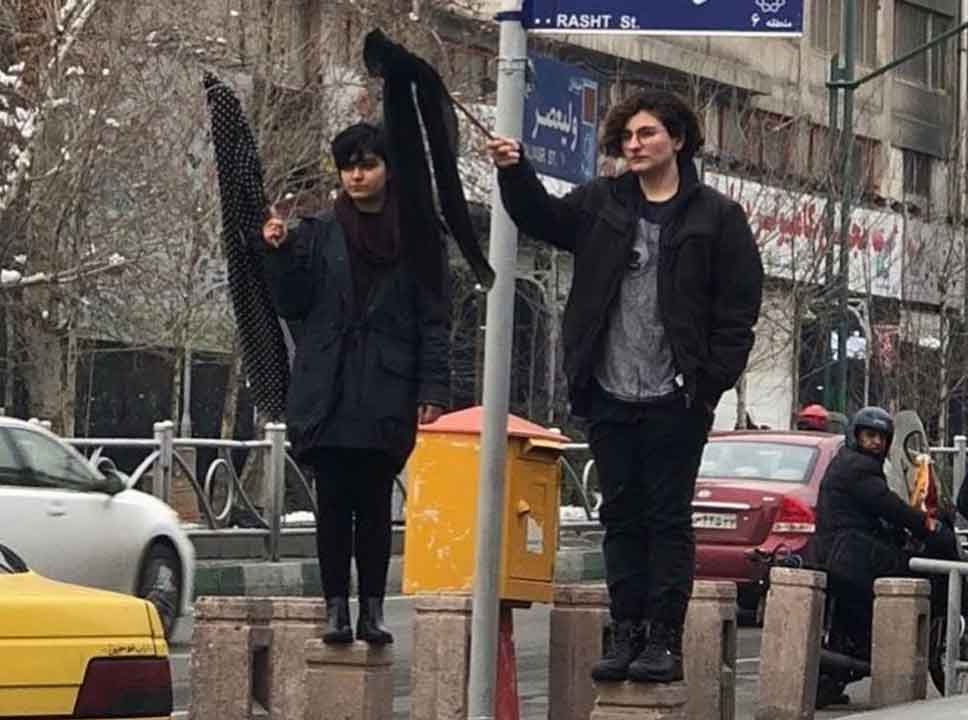

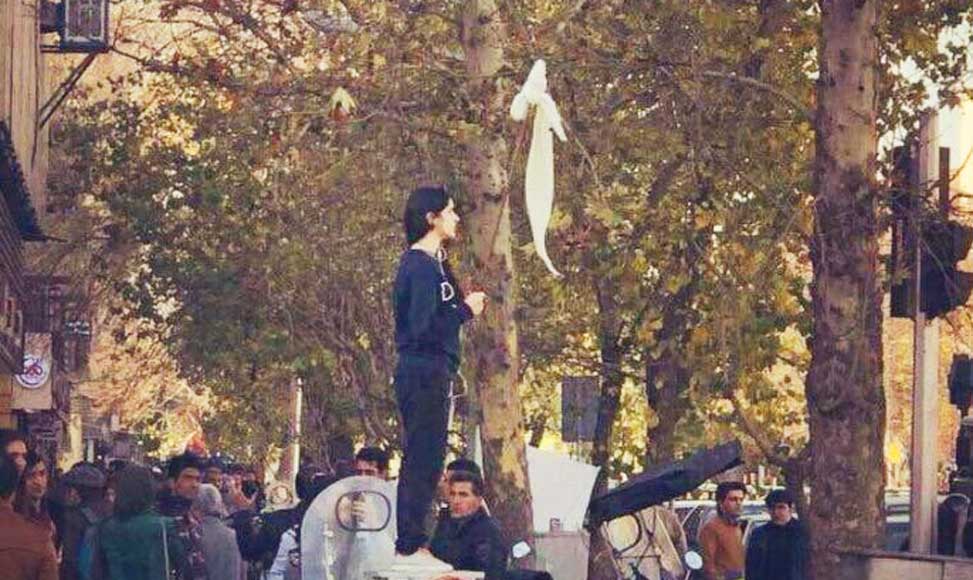

In January, Vida Movahed and dozens of other courageous girls and women around the country removed their headscarves and raised them on the end of wooden poles in protest against the mandatory hijab. Iranian society has persistently resisted the regime’s efforts to institutionalize the headscarf in the past four decades.

The simple, yet extremely powerful “Girls of Enqelab Street” movement caught the regime by surprise. It prompted some elements within the establishment to criticize the authorities for brutalizing the protesters. But their seeming support for the campaign is an attempt to exploit the situation for political gain.

Mohsen Hashemi, a leading reformist politician and the current Chairman of the Tehran City Council, believes that the regime has failed to institutionalize the hijab. “Our young people enthusiastically welcomed the hijab following the revolution, but the new generation doubts its merits and even opposes it. We have neglected our duty to educate our youth properly,” Hashemi said recently.

Hashemi fears that the Judiciary’s heavy-handed treatment of the protesters could have dire consequences for the regime. “We don’t prosecute people for failing to pray three times a day, even though it is an obligatory part of our religious faith. Similarly, the refusal to wear the hijab is a transgression that should be atoned for in private,” Hashemi noted.

The protest against the compulsory hijab is part of a broader global movement which advocates the rights of women to make decisions about their bodies and lives without fear, violence, and discrimination. Islam is not the only religion that has tried to deprive women of their human and civil rights. Christianity and Judaism have also been guilty of harmful discriminatory practices against women.

The struggle against the compulsory hijab is not a new development in Iran. Tahereh Qurratu I-Ayn [born in 1814, executed in 1852] and Hamida Javanshir [1873-1955] were among the earliest advocates of women’s rights in Iran. Some women chose to wear headscarves in the weeks preceding the Islamic Revolution. But the first significant protest against the compulsory hijab was staged less than a month after the revolution on March 8, 1979.

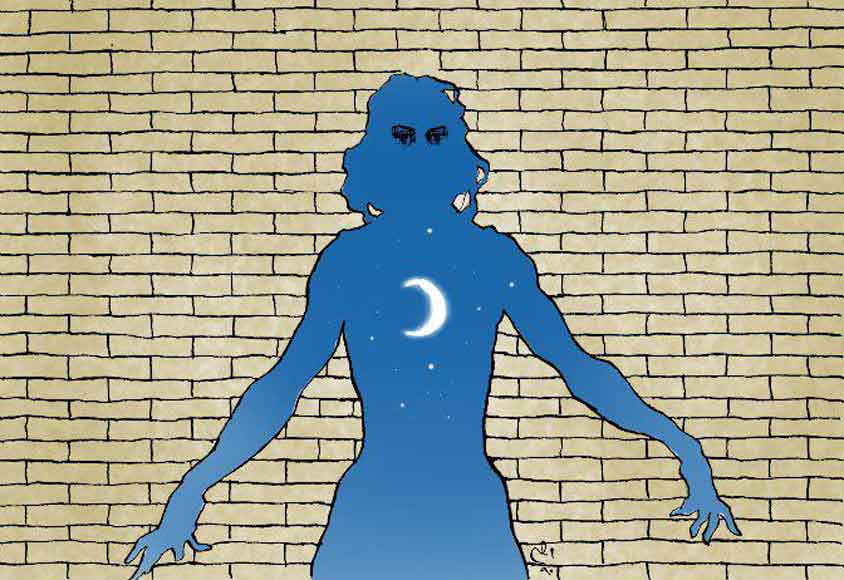

The “Girls of Enqelab Street” movement does not merely challenge the mandatory hijab. It also refuses to accept the regime’s definition of female identity within the Iranian society. Iranian women do not comply with the role assigned to them by a theocratic and undemocratic establishment. The Islamic Republic fears this new definition of female identity, which embraces freedom of choice. The brutal crackdown on the protesters has exposed the regime’s palpable fear of women’s hunger for freedom of choice. Therefore, the “Girls of Enqelab Street” movement should be understood in this context.

Hossein Shariatmadari, the managing editor of the Tehran-based hardline daily Kayhan, has been urging the regime to deal harshly with the protesters. “These movements are tools in the hands of those inside and outside the country who wish to incite unrest within our society,” a Kayhan editorial said. The column implies that the girls and women who bravely removed their scarves were targeting the heart of the regime.

“The police will deal decisively with these individuals,” Hossein Rahimi, Tehran’s chief of police, said. Rahimi’s statement shows that the regime feels threatened by the strength and scope of the protests. Even President Hassan Rouhani’s so-called reformist government of “Wisdom and Hope” cannot hide its fear of the growing social unrest. Salman Samani, the Interior Ministry spokesman, recently commented: “Inciting protest against the hijab violates Clause 2 of Article 639 of the penal code. The conviction carries a mandatory prison sentence of one to 10 years.”

The brutal crackdown on protesters, the imprisonment of women and the the suspicious suicides of many of the detainees in jail all point to the regime’s profound fear. The unwavering resolve of the courageous girls and women has posed an existential threat to the Islamic Republic. According to Nasrin Sotoudeh, a human rights lawyer, many women have been severely mistreated in jail, including Shaparak Shajarizadeh [who was arrested after removing her headscarf in public.] “It is unclear why Shaparak Shajarizadeh was injected four times with an unknown substance in jail,” Sotoudeh said.

The women in the “Girls of Enqelab Street” movement stood on telecoms boxes in protest to compulsory hijab. The authorities have now welded gabled tops to many of these boxes, making it impossible for anyone to stand on them. “We didn’t install these hoods as the result of the recent protests, but to prevent the theft of cables,” Mohammad Reza Bidkham, deputy head of the public relations office of the Public Communications Company, said.

It is clear that the installation of a few metal tops cannot dissuade courageous Iranian girls and women who have boldly challenged the regime’s despotic rule and medieval practices.

Thanks for a good article Mr Raafat

I believe we should not use the title of “Girls of Enghelab St” instead we have to use “daughters of Enghelab Street”. Girls and daughters have two different meanings in English. Girl mean an immature (non – Adult) woman which is not true for the women who protested against hijab. But daughter means the female child of someone which is suitable in this case.

In Farsi we have just one word for both but should not be mistaken when translating.