April 07, 2018

Reza Parchizadeh

Amir Naderi’s “The Runner” (۱۹۸۵) was among the first post-revolutionary Iranian films to attract worldwide attraction. It is considered by many to be a masterpiece of Iranian new wave cinema and one of the most important films of the post-modern era.

The film belongs to a select group of works that nostalgically recall adolescent adventures. Other memorable films in this genre include Federico Fellini’s “Amarcord” (۱۹۷۳), Giuseppe Tornatore’s “Cinema Paradiso” (۱۹۸۸) and “Malena” (۲۰۰۰). These filmmakers followed in the tradition of Italian neorealism of the 1940s and 50s.

“The Runner” chronicles the rite of passage experienced by the film’s protagonist, Amiro, a young boy who, at times, is a passive observer to the events unfolding around him. The film, however, doesn’t follow a linear storytelling style. It brings instead, a unique thematic and experimental approach towards action filmmaking.

Naderi’s film, which launched Iranian new wave cinema, is not a conventionally narrated visual tale. It is a bricolage of diverse and seemingly unrelated images, like the photographs in Amiro’s room, or a poem by Farrokhzad appearing on the screen for a fleeting moment. It focuses on thematic cohesion rather than a coherent narrative. At the start of the film, the audience sees snapshots of places, people and events that are repeatedly shown throughout the movie, including beaches, running boys, trash dumps and boats.

Locations and scenery reflect the harsh reality in which Amiro is growing up. The drama unfolds against the backdrop of crowded markets, filthy alleys, piles of giant pipes, oil platforms, industrial cranes, a busy port, massive tankers, abandoned rusted cargo ships, charred train remains, trucks, flare stacks, salt water, dust storms and cracked soil.

The story takes place in the city of Abadan, capital of the southwestern province of Khuzestan. But Naderi had to shoot the entire film in other locations very far from Abadan, which was engulfed by the Iran-Iraq War at the time. He, however, incorporated shots of the city’s recognizable landmarks in the film to authenticate the narrative.

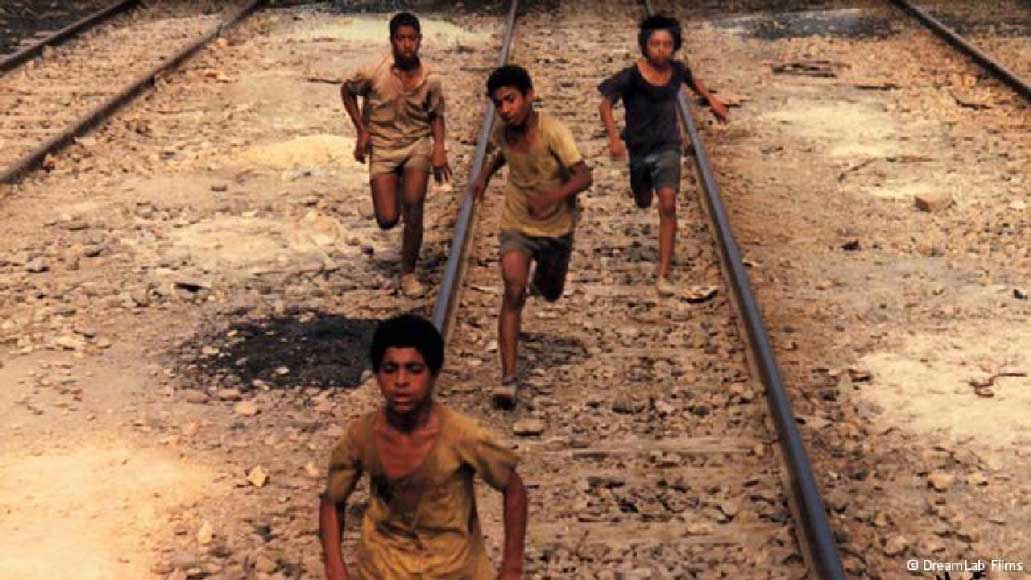

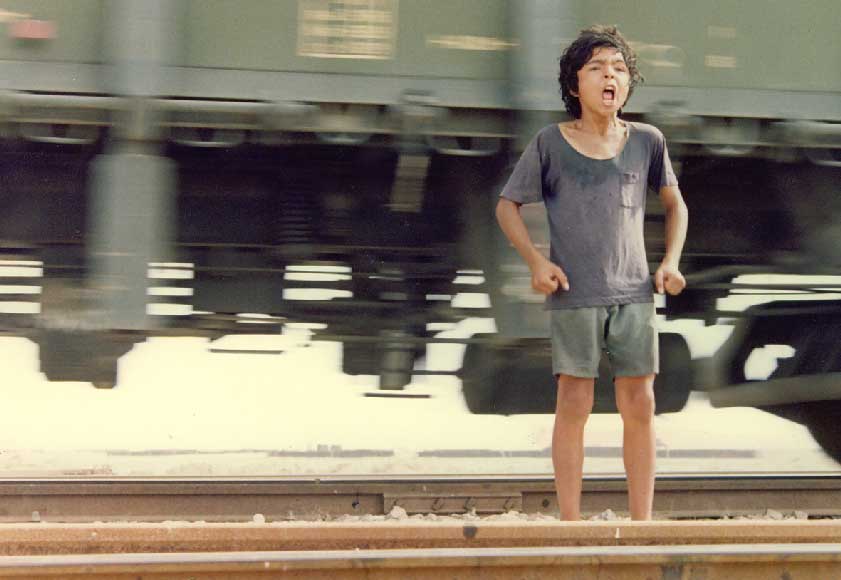

The central theme of the film is “running,” which symbolizes survival. It counteracts the existential fear of stagnation. Amiro is fleeing his desperate daily routines. There are repeated shots of swamps with stagnant water. Many other images evoke desperation and despair, including an old couple covered in the dust wondering far in the distance, a one-legged man walking into the sunset along railway tracks, and a train that vanishes into the horizon chased by playful children.

Naderi started as a photographer. Most of his films are in effect a series of still shots placed next to each other. He was the first post-revolution filmmaker who used this technique in feature films.

There is a poignant scene in which Amiro is running aimlessly between railway tracks engulfed in a dust cloud. Parallel tracks vanishing into the distance is a strong motif that is repeated all through the film. It represents life’s endless struggle. The film starts with two people fighting among a mountain of trash in a landfill. The daily struggle is a recurring theme in the movie. In another scene people battle over discarded bottle caps on the seashore.

To illustrate the unpredictability and brutality of everyday life, Naderi inserts images of natural phenomenon in the film including a sequence showing powerful waves pounding on the rocky shores, a devastating fire, and scorched earth. In Naderi’s brutal existential world, man competes against unforgiving nature. To survive, he must win. And the winner takes all.

The final sequence which depicts the climax to the race is a masterpiece of directing and editing by Naderi and Bahram Beyzai, respectively. The audience accompanies the runners every step of the way, feeling their struggle, anxiety, anticipation, desperation, and triumph. The ending of “The Runner” reminds me of the chariot race in William Wyler’s 1959 epic movie Ben-Hur. The final stretch is brutal with each competitor trying to eliminate his opponents. The runners push, shove and try to trip one another hoping to be the first one to cross the finish line.

The winner is not rewarded with a tangible prize but achieves a moral and symbolic victory. For Amiro, the race is a journey of self-discovery. He faces enormous obstacles and daunting challenges but triumphs and emerges as a young man at the end. He passes the last test by sharing his prize of ice and cold water with his fellow competitors. And in that moment and through a selfless act of generosity and compassion, Amiro becomes an adult.

Naderi and Beyzai (editor of “The Runner”) were among a handful of pioneer filmmakers who placed more emphasis on form than content. For them, a film is not a mere vehicle for telling a story, but rather a compelling visual experience.

More than a century earlier, proponents of the literary, artistic and philosophical school of Formalism — including Ezra Pound (American, 1885-1972) and T.S. Eliot (British, 1888-1965) — focused on structure, modes and forms. They were major figures in the early modernist movement, and made significant contributions towards developing “Imagism” (poetry that favored precision of imagery and clear, sharp language). These literary giants were inspired and influenced by Charles Sanders Pierce (1839-1914), an American philosopher (also known as the father of pragmatism) and Henry James (1843-1916), an American author. Instead of lengthy explanations, their works rely on visual narrations.

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein (Russian, 1898-1948), German Expressionist filmmakers and other European modernists were early practitioners of Imagism. They effectively used montage and mise en scene and other techniques to create a unique cinematic language. Prominent filmmakers of the silent era, including Fritz Lang (German, 1890-1976) and F.W. Murnau (German, 1888-1931), used fantastic imagery for dramatic visual effect.

Many Iranian artists, poets, and philosophers embraced European modernism, including Nima Yooshij (Poet, 1987-60), Forough Farrokhzad (poet, 1935-67), Ahmad Shamlou (poet, 1925-200) and Sohrab Shahid-Saless (filmmaker, 1944-98). They and others produced some of the best examples of Imagism in the 1950s and 60s.