May 01, 2018

By Nosrat Vahedi

In an opinion piece entitled “Where is Iran heading?” published by Kayhan London on April 17 [see translation], Dr. Fazel Gheibi wrote: “Before the Islamic Revolution, the national will was focused on removing the Shah who had failed to establish democracy in the country. The movement was collective and just, but lacked intelligence and wisdom. Iranian intellectuals were unable to transform democracy as a political idea into a popular social cause.”

The concept of the “general will” or the “collective will,” which was put forward by French

philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (۱۷۱۲-۱۷۷۸), refers to “public welfare.” Rousseau is contrasting two theories: a credible view of human beings, and an intellectual perspective.

On the one hand, Rousseau encourages people to challenge authority, and on the other hand, he supports the idea of filling the vacuum left after the departure of the ruling regime with another governing system. He attributes this responsibility to the “general will.”

Rousseau, however, knows that the “general will” must not operate unchecked, and must be used wisely. The only way to realize the “general will” is through elections or legislation. Parliament has the difficult task of mediating between the governing power and the people. Rousseau believed that people and the Parliament should take a transparent, coherent, logical and impassioned approach towards achieving their objectives.

The concept of the “just will” which Dr. Gheibi has alluded to doesn’t exist. The word “totalitarian” might have had a special meaning in the past, but it has no place in the 21st-century lexicon.

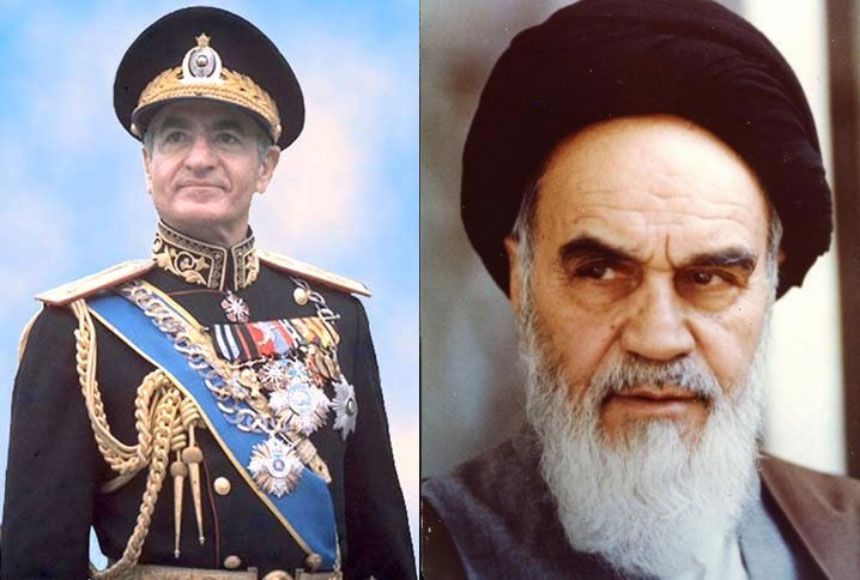

The Islamic Revolution never promoted justice. Rousseau’s “general will” can never be realized as he had envisioned it. In 1979, the “general will” was manifested as fascism. Fascism oppresses and brutalizes the public. It never allows democracy, meaning “rule by the people,” to take root in a country. The experience of the Iranian people in the past 40 years confirms this.

In his article, Dr. Gheibi offers not an analytic view, but rather a subjective view of the 1979 Revolution. Additionally, Iranian intellectuals such as Dr. Gheibi should have asked the question “Where is Iran heading?” back when the mosques were urging young people to march in the streets. The so-called intellectuals stayed on the sideline and watched the protests in amazement. The merchant class and the left supported the demonstrations. Why didn’t they hear the sound of the marching fascists? It is too late now to ask ‘Where is Iran heading?’ The person who asks this question has nothing of substance to say.

Dr. Gheibi speaks of the late Shah’s ineffectiveness. Only a person who has successfully advanced democratic principles can criticize the Shah for failing to establish democracy. We, as a nation, are still struggling with the whole idea of a free society. It is outrageous to judge the Shah’s reign based on Rousseau’s 18th-century notion of democracy. Offering a handful of examples to support this theory doesn’t prove the point. Every country has its peculiar history. One cannot compare European countries, which experienced the Renaissance, Humanism and the Reformation from the 14th to the 18th centuries, with Iran. India was a British colony for more than a century. It learned a lot from the British during that time.

During the reign of Reza Shah (1925-1941), the authorities had dug ditches around the capital Tehran and placed 12 gates around the city to control the flow of people. At the time, Tehran had no sanitation department, electricity grid, telephone lines, or water and sewage systems. It was a segregated city, divided along religious and ethnic lines.

Dr. Gheibi believes that Iran has been fighting for democracy for the past 200 years and that our culture is devoid of any prejudice. He says: “We don’t understand the true nature of democracy…Under Pahlavi rule, the nation relied on its historical and cultural identity to avoid any tribal, ethnic, racial and religious conflict.” These are wrong assumptions. Political leaders didn’t provide a comprehensive plan to the Shah for establishing democracy in Iran. They were mere pawns in the political chess game.

I visited the late Dr. Ali Amini (former Prime Minister 1961-62) at his house in summer of 1978. I asked him why he didn’t want to become a Prime Minister. He said that the “boss,” meaning the Shah, wasn’t happy with him, and that those who pulled strings favored Mr. Shapour Bakhtiar (Prime Minister January to February 1979). The same powers gave $150 million to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini who was in France at the time. It wasn’t the Shah who was weak, but our society that has a 1,400-year history of not being able to determine its fate.

It is not the “general will” but the innate determination of individual members of a society that paves the way for the rule of the people. We cannot apply Rousseau’s ideas to the modern world. I’m somewhat puzzled as to why Dr. Gheibi has not referred to any of the contemporary theories that are more relevant to the current political climate.

Dr. Gheibi also states: “Iranians have historically preferred peace and forgiveness over hostility and retaliation.” We Iranians wear our culture like a badge of honor. Some of us assume that culture evolves for the better. But history has shown us otherwise. There is not a single culture in the world that has consistently grown upward. Iranian rulers have committed horrible atrocities, both before and after the Muslim invasion of the country in the 7th century. Our country experienced intense tribal and religious conflict during the reign of Reza Shah. We also witnessed an increased number of violent armed attacks in years preceding the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Unfortunately, nepotism and superstitions have shaped post-revolutionary culture. The culture of “insider-outsider” dominates the Iranian society. Freedom of speech and of the press are the pillars of modern democracy. The media in Iran only publishes pieces by the regime’s insiders. Newspapers routinely censor articles by writers who are deemed to be outsiders. We used to criticize the Shah for restricting freedom of speech and press, but today we self-censor. That’s the difference between the West and the East. They don’t appreciate scientists and experts during their lifetime, but build shrines for them after they die.

People from different ends of the political spectrum celebrated in the streets after Reza Shah and Mohammad Reza Shah were forced into exile in 1941 and 1979, respectively. But recently the young protesters were shouting “We want the Shah.” This example illustrates the contradictions in our culture.

In Iran, most families, irrespective of their economic circumstances, hire tutors for their children. The pupil-mentor tradition is deeply rooted in the Iranian society, not just in schools but also in workshops, stores and factories. But the culture has gradually disappeared. Many university professors, master artisans, and teachers just stopped mentoring students. In the West, however, the student-teacher interaction is an integral part of the education system.

Only a few public holidays, most notably Nowrouz, are being celebrated nowadays. Nowrouz marks the coming of a new year, meaning out with the old and in with the new. Iranians are, therefore, not traditional by nature. They have always celebrated social change. Nowrouz is the only remnant of what once was a dynamic culture. It is a hollow symbol of a glorious era long gone. Visiting relatives and friends during the Nowrouz holidays was a way of strengthening ties through communication.

Interactions and exchange of ideas pave the way for resolving disputes. We witness this culture in the West these days. Progress is only possible through innovation and change. German sociologist and philosopher Jurgen Habermas (1929 – ), believes that effective communication is the basis for successful negotiation. We can trace this idea back to ancient Iran.

Dr. Gheibi has speculated that if a referendum were to be held in Iran today, the 40-year struggle for democracy and freedom would end, and Prince Reza Pahlavi might win. “He would most likely reinstate the same hereditary monarchy as his father, the late Mohammad Reza Shah,” Dr. Gheibi cautions. I’m not certain what Dr. Gheibi means by the 40-year struggle for democracy. By readily dismissing Reza Pahlavi as a viable opposition to the current regime, Dr. Gheibi ignores the young people who were recently shouting in the streets “We want the Shah.”

I’ve always maintained that the left and the Tudeh Party (the Iranian Communist Party) are reactionary. The Iranian people, who have hung on to the last vestiges of noble Persian tradition, are the flagbearers of real democracy. Our understanding of a free society differs in many meaningful ways from that of the 20th century. In the same way, we have a different view of monarchy than those who are stuck in the previous century.