May 21, 2018

By Firouzeh Ramezanzadeh

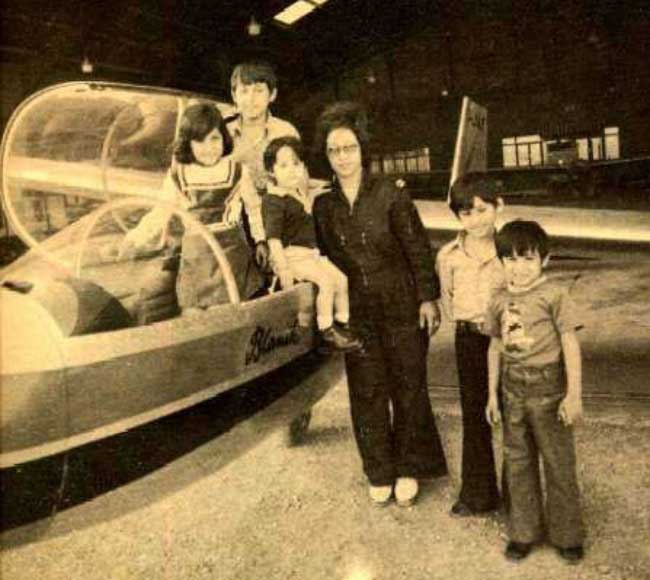

Akram Monfared-Ariya was born in 1946 in Tehran. She is a pilot, poet, painter and author who currently lives in Sweden.

Ms. Monfared-Ariya and the late Princess Fatemeh Pahlavi (1928-1987, the late Shah’s half-sister) were the only two Iranian women who held a pilot license and were certified to fly single-engine aircraft.

Monfared-Ariya was only 16 years old and still in high school when she got married. After receiving her diploma, she studied English at the university. It took another ten years before she became interested in piloting airplanes.

Monfared-Ariya completed her sailplane, glider and no-engine flight training at Shahanshahi Flight Club at Doshan Tapeh Airbase, south of Tehran. She subsequently enrolled in the flight training program at Qala Morghie Airport, Tehran and obtained her pilot license for single-engine aircraft.

Air Aseman hired Monfared-Ariya as a co-pilot, but the 1979 Islamic Revolution dashed her dreams of pursuing a career in aviation. She eventually left Iran with her five children and settled in Sweden.

Monfared-Ariya is a member of the Swedish Writers’ Union. She has published 16 books in Swedish, English, and Farsi since 1999. Three of her books have been translated into English and published as e-books in Canada. They are available to readers free of charge.

The following is Kayhan London’s interview with Monfared-Ariya:

Firouzeh Ramezanzadeh: Ms. Monfared-Ariya, why did you become a pilot?

Monfared-Ariya: I was 26 years old at the time, and had five children between the ages of two and 11. I saw a TV ad in which two people were flying a single-engine aircraft. I said to my husband that I was sitting home idle while others were doing something with their lives. My husband, who was a liberal thinker, asked if I was interested in learning to fly an airplane, to which I answered yes. He replied: “Then go for it.” He never thought that I would pursue it.

The next morning, I called and made an appointment with the Shahanshahi Flight Club. I told my husband about it when he came home that night. He said: “Try it. It’ll be wonderful if you succeed, and if it doesn’t work out, at least you won’t have any regrets.”

People at the Shahanshahi Flight Club were delighted to see a woman interested in learning to fly an airplane. But they were concerned that I had five young children because as they pointed out “flying an aircraft was a dangerous activity.” I said to them that danger lurked everywhere and that I could die at any time and anywhere.

I started my training with a glider and accumulated many flight hours at Doshan Tapeh Airbase. I was able to obtain my pilot license for no-engine planes after only three months. Subsequently, I received more training at Qala Morghie Airport and made my first solo flight, after which I underwent an initiation ceremony of being doused with water.

Q: Was that an old tradition?

A: Yes. When I landed the plane, club members were waiting for me with big buckets of water. I flew various single-engine aircraft at Qala Morghie for four years including Cessna and Bonanza. I was also set to receive training as a co-pilot on twin-engine planes.

Q: Did anyone else in your family, besides your husband, support your decision to become a pilot?

A: Yes. Everyone was happy for me. My mother used to say that whenever she heard an airplane, she’d pray that I’d land it safely. I told her that I wasn’t flying every single aircraft she saw in the sky. My uncle couldn’t understand why I had decided to become a pilot instead of a nurse or a teacher. I told him that the world was full of nurses and teachers, but there weren’t any Iranian female pilots.

Q: Have you ever had an accident?

A: I’ve never been in an accident. On one occasion after launching the glider, I tried contacting the tower and let the air-traffic controller know that I was about to detach the cable from the ground-based winch. But I received no instructions from the control tower. They finally noticed the problem and cleared the runway. I was finally able to put the glider down, but it wasn’t a smooth landing. My whole body was shaking with fear.

Q: There must have been other Iranian women who were interested in becoming pilots. How far did they get in their training?

A: More than 200 Iranian girls and women had received their glider license before me. But they did it mostly for fun and weren’t serious about it. But I pursued it in earnest despite having five children and running my insurance company. I even received two job offers one as a flight instructor and the other co-piloting twin-engine planes for Air Aseman.

I spoke to Mr. Kambiz Dadsetan, the director of Air Aseman about the co-pilot position. Right before starting the job, the Islamic Revolution happened. Subsequently, the regime imposed more stringent restrictions on women. My children and I left Iran for Sweden. I resumed flying airplanes and obtaining my Swedish license. But I wasn’t able to find a job as a pilot due to Swedish laws and regulations.

Q: Why did you have to leave Iran after the revolution?

A: The revolution turned our lives upside down. My husband, father, brother-in-law, uncles and other family members lost their jobs. The regime banned them from engaging in business or leaving the country. The authorities accused my uncle (mother’s brother) of working for SAVAK (the late Shah’s secret police) and threatened to execute him. He was eventually cleared of all charges and released. He and my brother-in-law were army officers. My father was an architect, and my husband was a trial lawyer.

My eldest child, Ali, is only 17 years younger than me. He was refused entry to university because the regime deemed our family “anti-revolutionary.” The war with Iraq had broken out, and young men couldn’t get into university or marry unless they had served in the military. So he joined the army. Those were tough times for me. The army deployed his unit to the front-line near the Iraqi border. He would come home whenever he was on leave. During one of those visits, Ali said that the army was going to deploy his unit to Marjan Island. Many young Iranian soldiers had died on that island. Hearing that I said to my son that the only way they’ll send him to that island would be over my dead body.

We were able to find someone to help us. The so-called “smugglers” are really “rescuers.” I respect the person who saved my children’s lives. I’m eternally grateful to him, even though I had to pay for his services. I took Ali to the Turkish border where he met the smuggler who arranged his journey to Turkey where he stayed for six months before going to Sweden. My son and I couldn’t say goodbye at the border because we had to pretend we didn’t know each other.

Q: Didn’t you get into trouble for sending your son, who was a soldier, abroad?

A: The army and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) considered my son a deserter. They came to our house looking for him. We changed our address many times. While Ali was in Turkey, I underwent surgery at a hospital in Tehran to remove a cancerous tumor. My daughter told me that the military had revisited our house looking for Ali. I left the hospital and went directly to the military HQ. I discovered that the army had listed Ali as missing in action.

Q: How did you get the rest of your family out of Iran?

A: I used the same smuggler to send my two other sons to Sweden via Turkey in 1984. I traveled to Turkey 14 times during this period. The authorities even banned me from leaving the country. But I was able to go with my 11-year son to Turkey. I used the same smuggler to send my son to Sweden via Bulgaria and Germany in spring of 1985. A few young Iranian men were also traveling in the same group as my son. When I returned home, I discovered that my husband had died the week before. Soon after, my daughter and I left Iran. She went to Canada, and I made my way to Sweden in autumn of 1985.

Q: How were your first years in Sweden?

A: I enrolled in a language school right away. All my children were going to school at the time. Within a year I got a job at a bakery working night shifts. I worked around the clock that whole summer. I was finally able to get a bank loan and open a small restaurant selling pizza and Turkish kebab. The local newspaper ran a story on me as the first female owner of a pizzeria. I moved to Stockholm after my children enrolled in universities. I pursued my dream of becoming a writer and published my first book in Farsi in 1999. I released my memoirs in 2012. I’ve written 16 books to date; four in Farsi, one in English and the rest in Swedish. I’ve also been painting with oil, acrylic, and watercolor since 2007. I have shown my work at numerous exhibitions in Sweden.