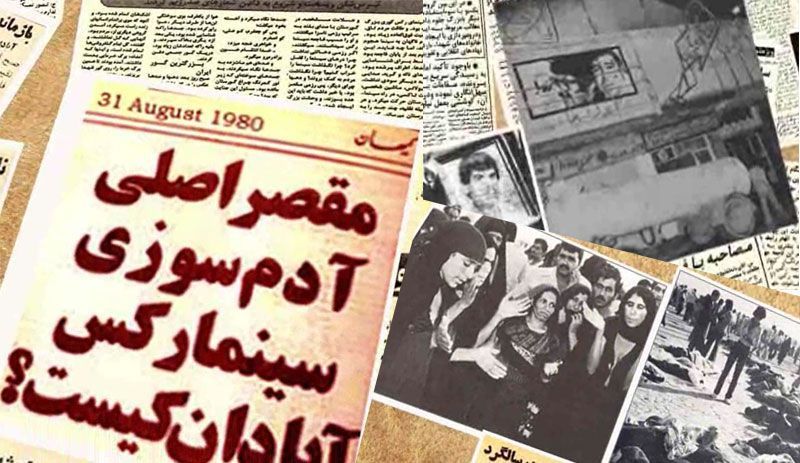

August 19, 2017

By Potkin Azarmehr

Thirty-nine years ago today, 470 innocent people were burned alive inside the movie theatre in southwest Iran. The movie theatre on the first floor of a shopping arcade. Victims included entire families: mothers, fathers, children and siblings who should have spent a fun day together at the movies.

On 19th August 1978, Cinema Rex in the city of Abadan in the Khuzestan province in south west Iran, was set ablaze by fanatic followers of Ayatollah Khomeini. Despite all the terrorist attacks around the globe since that day, the fire at Cinema Rex still ranks amongst the top five worst terrorist attacks worldwide. Yet this mother of all terrorist acts against ordinary innocent people remains largely unknown outside Iran.

For Khomeini and his followers, cinemas were a symbol of decadence. In their medieval mindset, cinemas promoted corruption and prostitution. Since the inception of the Islamic Revolution in January 1978, when a few seminary students had protested against an article that derided Khomeini’s Indian origins and his reactionary views, Islamists had unabashedly burned down more than two dozens cinemas across Iran. Yet when cinema Rex was set on fire, the Shah’s opposition -the Islamists, the Communists and the liberal National Front- blamed the state secret police, SAVAK for the tragedy.

For Khomeini and his followers, cinemas were a symbol of decadence. In their medieval mindset, cinemas promoted corruption and prostitution. Since the inception of the Islamic Revolution in January 1978, when a few seminary students had protested against an article that derided Khomeini’s Indian origins and his reactionary views, Islamists had unabashedly burned down more than two dozens cinemas across Iran. Yet when cinema Rex was set on fire, the Shah’s opposition -the Islamists, the Communists and the liberal National Front- blamed the state secret police, SAVAK for the tragedy.

The National Front accused the Shah of being behind the arson attack inorder to justify a crackdown on the opposition. The Front likened the Rex fire to the burning of Reichstag in Berlin. The international media, in love with the Shah’s adversaries, fell for the narrative hook, line and sinker. The Shah’s men, incompetent and indecisive, were no match for the opposition’s propaganda skills. Indeed the culprit who had lit the match, Hossein Takbalizadeh, had turned himself in and was in custody.

The fake news of that era would have survived to this day, but for two eventualities. First, the families of the victims demanded a public trial and refused to keep silent after the revolution. As importantly, the tormented perpetrator admitted to his crime during the public trial. He refused to be coerced into giving the revolutionary narrative or seeking remission in the punishment he deserved.

The protests that had began against the Shah in January, 1978, had largely been confined to the religious cities in Iran and Abadan, a cosmopolitan city with the world’s largest oil refinery and Iran’s main petrochemical industries had played no part in the sporadic disturbances before the fire at cinema Rex. Even in the religious cities, the protests seemed to be running out of steam and the Islamists needed to reignite the protests to keep the momentum going.

It all came down to a petty thief and a drug peddler by the name of Hossein Takbalizadeh to change the course of history for worse. Takbalizadeh was a trained welder but mostly he hung out with his chums and dealt heroin and hashish. He had previous arrests and jail sentences for theft, assault and arson too. At some point he was introduced to radical Islam by someone in his neighbourhood, called Asghar Nowruzi. Together they would go to a religious centre in Abadan, called Hosseinieh, where they made other like minded comrades.

Takbalizadeh was sent to a clinic in Isfahan to cure his addiction. There he was introduced to more revolutionary religious literature. He returned to Abadan with a suitcase full of subversive literature and tape recordings of Khomeini’s fiery sermons.

Upon his return to Abadan, Takbalizadeh and his friends from Hosseinieh were further incited by Kiavash, a school teacher who was a Khomeini devotee. Kiavash told them, “the youth from other parts of Iran have sent you women’s underwear to wear because they don’t think you are man enough in Abadan. Everywhere else in Iran, the youth are taking action against the Shah but not in Abadan”

Takbalizadeh and three of his friends, Faraj, Yadollah and Fallah decided to set a cinema on fire to fan the flames of the Islamic revolution in Abadan. They first went to Soheila cinema. They filled four used drink bottles with paint thinner and poured it over the lobby but it did not catch fire. Takbalizadeh, who had previous experience of arson, recognised that the problem was because the paint solvent they used evaporated too quickly. They decided to add cooking oil to stabilise the solvent. They went back to Soheila cinema but by then it was closed. They planned to come back the next day but intoxicated with revolutionary zeal to do God’s work, they remembered another cinema opposite the municipality, that was Cinema Rex.

They bought skews of liver kebab to eat before the next show. As they watched their liver kebabs cook over the charcoal grill, little did they know they will soon be responsible for more than 400 innocent people burn to death.

Halfway through the film all four went to the lobby. In the absence of any cinema officials there, they poured the solvent on the wall and on the floor and Takbalizadeh lit the match. The flames quickly engulfed the lobby first and then spread to inside the theatre room, many died in their seats suffocated by the poisonous gases. Takbalizadeh himself escaped by the main stairs but the other three perpetrators died too.

Takbalizadeh, agonized and tormented by the terrible crime he had committed, confessed his crime to his friends and to his mother and later to the police who had arrested him for taking part in a brawl, but by then the Shah’s government was totally dysfunctional and the revolutionaries were controlling the events.

After the revolution’s victory, when the prisoners broke loose across Iran, Takbalizadeh too escaped and travelled all the way to Tehran to confess his guilt. He tried to see Khomeini but he could not pass through the crowds at Alavi school to reach him. The interior minister of the new revolutionary government also turned him away. The men who had provoked and manipulated him were now the dignitaries of the new regime, they told him to go away, keep quiet and forget about it.

Finally when the pressure from the families of the victims forced the new regime to hold an open trial, Takbalizadeh wept and confessed everything in front of the public. The cleric judge, Moussavi-Tabrizi and the prosecutors made a great effort to blame the fire on the Shah’s secret police and convince Takbalizadeh that he was manipulated by the agents of the ancien régime led by their American and Israeli puppet masters. The prosecutor even tried to claim the fluid used to set the cinema on fire was military grade fuel only accessible to governments.

Takbalizadeh was not bartering for his life. He had just one wish: to confess and ease his conscience. If Takbalizadeh did one thing worthwhile in his entire wretched life, it was the courage he showed in that trial to tell the truth as it was.

Aristotle said “When great interests are at stake, revolutions are often caused by trifles”. The trifle in the 1979 revolution in Iran, was a petty criminal called Takbalizadeh. Fortune was riding with the revolutionaries. Terror had paid them handsome dividends. They had got away with burning people alive. They had managed to fool the intellectuals, the media and the world. So much so, that the US ambassador to Iran, William Sullivan, referred to Khomeini as a “Gandhi-like figure” and US Ambassador to the UN at the time, Andrew Young, said “Khomeini will eventually be hailed as a saint”!

Terrorism had won hands down.